Outdoor Hour Challenge: Pileated Woodpeckers

Back in mid-April, my daughters and I stumbled upon a pileated woodpecker nest on one of our walks in the woods. We noticed not one, but two adult birds on a dead tree. The female flew away; the male went inside.

When we went past the spot in subsequent weeks, it seemed like nothing was going on there. But more recently it has become apparent that it was — and is — an active nest after all.

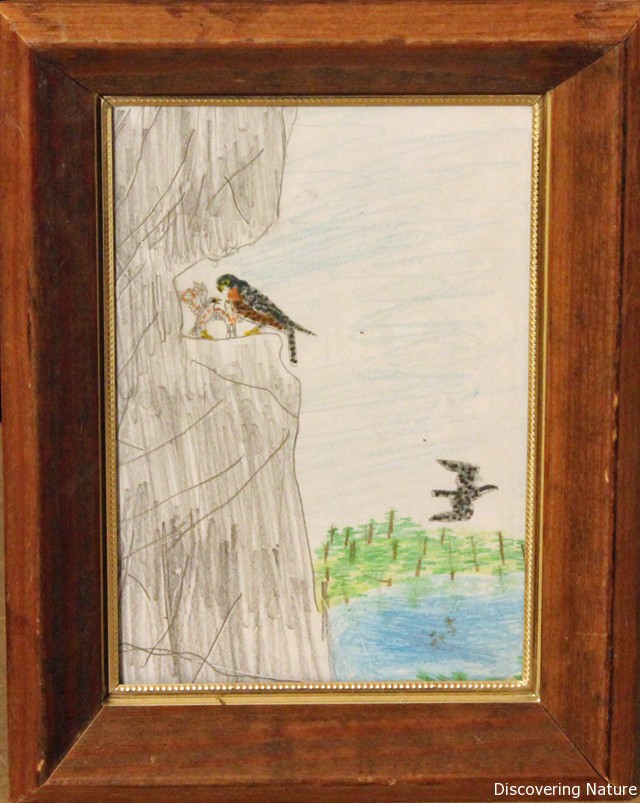

This is the female woodpecker, nearly as large as a crow, preparing to feed. The youngsters are a male (with the red sideburns), and a female (with black sideburns).

The male adult has more red overall — a red crest that reaches all the way down his forehead, and red sideburns.

I’ve posted some pictures of feeding here, and of a nest exchange here.

I’ve posted some pictures of feeding here, and of a nest exchange here.

The girls and I compiled a list of the most interesting things we’ve learned about pileateds:

- Their tongues coil all the way around their skulls and are long, sharp spears with backward-facing barbs that can be extended and retracted.

- Zygodactylus feet — two toes face forward, two face backward. (A fun new word to pull out from time to time!)

- The nestlings’ solid waste is in small packets that the parent birds carry away. (I witnessed this one morning after a feeding.)

- They are “forest engineers,” excavating cavities that other birds and mammals use for their homes.

- Their call sounds like the wilderness. One of their nicknames among the early settlers was “the laughing woodpecker,” and they do have an wild-sounding laugh — it makes me think of Bertha Rochester in the attic (Jane Eyre).

- A normal clutch is four eggs.

- The parents feed by regurgitating from their crops directly into the eager beaks of their young.

- The male ends up doing the majority of the incubating.

- They have sleeping cavities in trees, and often these holes have escape routes.

- One of their main foods is carpenter ants.

Though my reflex is to think of them as wilderness birds, they have adapted quite well to human “landscape engineering.” I know of three pairs nearby, so I guess this provides some anecdotal evidence. They’re often compared to ivory-billed woodpeckers, which have fared very differently and are now, probably, extinct.

Our favorite resources, in addition to observation, have been this website and several books, of which this one has been the most complete.

I remember hearing a pileated woodpecker while riding my bike a year ago, and working hard to get my first picture of one. It was far away and a little blurry, but I was completely thrilled. I never would have guessed the sights we had in store for us this year. If the trees had been fully leafed-out, we probably wouldn’t have seen this pair that day in April. And though the young make quite a racket begging for food when their parents are near, we might chalk the strange sound up to something else if we didn’t know the source. It’s been a good reminder for us to keep an open mind and alert senses in the woods.

I’m submitting this post to the Outdoor Hour Challenge, a great round-up of nature-study postings each month.

4 Comments

Barb-Harmony Art Mom

What an exciting long term project to watch this nest and now the young ones. I now know how to tell the male and female birds apart thanks to your very interesting post. I also found it interesting that their main food is carpenter ants…that must be a lot of ants.

Thanks so much for sharing your study and your wonderful journals too.

Janet

Yes, it must take a lot of ants to fuel such a big bird!

crafty_cristy

I love this post. Thank you for sharing your family’s experience with nature!

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

Wonderful. 🙂